27. The Apostles Could Not Have Created the Lord’s Day

John 4:24, Gal 4:9-11, Rev 1:10

The Greek text of Rev 1:10 tells us that John was “in spirit in the Lord’s Day.” He was not “in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day,” as we read in all English translations. He was taken in spirit into the future.

In Greek, one is “in a day” and not “on a day, and many believe that the “Lord’s Day” in Rev 1:10 described a weekly meeting time established by the apostles. They cite the fact that the church came together to break bread on Saturday night in Acts 20:7, and they cite Paul’s instruction to set aside offerings on the first day of the week in 1 Cor 16:2. But neither of these verses provide evidence of a special weekly meeting. Acts 2:46 tells us that the early church met daily to break bread, and the setting aside of offerings on the first day of the week was a practice from the Old Testament.

You observe days, and months, and seasons and years. I fear for you that perhaps I labored for you in vain.

Galatians 4:10-11

The apostles could not possibly have created a religious day for worship. Jesus told us that the Father is seeking true worshipers who will worship Him in spirit and truth, “neither in Jerusalem nor on this mountain”John 4:24 —not according to a time or place, which Paul called worship, according to “the elementary principles of this world.”Col 2:8 Paul asked the Galatians, “How is it that you have come to know God … but return to the weak and worthless elemental things? … You observe days, and months, and seasons and years. I fear for you that perhaps I labored for you in vain.”Gal 4:9-11 Paul admonished the Galatians not to observe religious days with the Jews, saying, “If anyone brings you another Gospel, let him be eternally condemned.”Gal 1:8-9 Jesus called those who say they are Jews but are not “a synagogue of Satan.”Rev 2:9 Rev 3:9

After Jesus was made the Lord in the New Testament, the apostles used the expression “Day of the Lord” to refer to the day of Christ’s return. The apostle John used the expression “Lord’s Day” in Rev 1:10 to signify the Day of God—the Day when God becomes the Lord again.

28. False Translations of the Lord’s Day

In the book From Sabbath to the Lord’s Day, A. T. Lincoln wrote, “Of the New Testament texts it is only Revelation 1:10 with its designation of the first day of the week as the Lord’s Day that can indicate the theological significance that was attached to this day.”1

A. T. Lincoln has assumed, however, that “the Lord’s Day” in Rev 1:10 is speaking of a weekday and not of the Day of Christ’s return.

The Greek text tells us that John was “in the Lord’s Day,” not “on the Lord’s Day.” Of course, A. T. Lincoln knows this, but many other false translations of early writings have led us to believe that “the Lord’s Day” in Rev 1:10 refers to a weekday. In the 16th century, Ussher translated “Lord’s life” in Ignatius’s Letter to the Magnesians as “Lord’s Day.” Others replaced “Lord’s Word” with “Lord’s Day” and “Lord’s Holy Day” with “Lord’s Day” in Eusebius’s Church History. In 1912, Kirsopp Lake added “Lord’s Day” to the translation of The Didache, where the Greek inferred “Lord’s commandment.”

For I say to you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 5:7

Besides these false translations, there are many manuscripts falsely attributed to bishops and apostles that describe the “Lord’s Day” as a weekday, but all these were written or rewritten in the 4th century or later.

Once we remove all the fraudulent writings, the truth of the “Lord’s Day” is easy to see. The expression “the Lord’s Day” did not refer to Sunday until the 4th century.

At the end of the 2nd century, the churches of Egypt and North Africa began to celebrate the end-time resurrection of the saints on “the Lord’s Day,” Easter Sunday. It was not until A.D. 325 that the church in Rome made every Sunday a celebration of the resurrection of the saints. In fact, some 2nd-century believers used the expression “the Lord’s Day” to refer to the Sabbath Day—“the Lord’s Holy Day.”

29. The Annual Celebration of the Lord’s Day

At the end of the 2nd century, the churches of Egypt and North Africa began to call the annual celebration of the resurrection of the saints “the Lord’s Day,” but it did not become a weekly celebration until the 4th century.

It seems that the annual celebration of “the Lord’s Day” began after the Quartodeciman controversy. In A.D. 193, the bishop of Rome wrote letters of excommunication to the churches of Asia because they did not accept his doctrine of Easter Sunday. In this debate, Bishop Polycrates said that he could only remember the Passover on the 14th of the month, according to the Old Testament instruction: “We observe the exact day, neither adding nor taking away. For in Asia also great lights have fallen asleep, which shall rise again on the day of the Lord’s coming.”2

Behold He is coming with the clouds, and every eye will see Him

Revelation 1:7

The churches of Asia did not actually celebrate the resurrection: they remembered the Passover. But perhaps in response to the Quartodeciman debate, the churches of Egypt and North Africa began to celebrate the resurrection of the saints, who will rise on the Lord’s Day. They called this annual celebration “The Lord’s Day.” Tertullian described it as the anniversary of the birthdays of those who will resurrect: “As often as the anniversary comes around, we make offerings for the dead as birthday honors.”3 In Egypt and North Africa, the expression “the Lord’s Day” was used only in the context of the Easter celebration. Origen listed the days of the resurrection season as the Lord’s Day, the Preparation, the Passover, and the Pentecost.4 Both Origen and Tertullian compared the significance of the Lord’s Day to that of the Day of Pentecost.5

By the 4th century, the churches throughout the world were calling the annual celebration of the resurrection “The Lord’s Day.”

In A.D. 324, one year before Rome called every Sunday “the Lord’s Day,” Eusebius, the bishop to the emperor, described “the Lord’s Day” as the time to celebrate “rites like ours in commemoration of the Savior’s resurrection.”6 Of course, these were not rites that were performed on a weekly basis.

30. Jesus Rose on a Saturday

Many believe that Jesus rose on a Sunday, and that is why Christians celebrate on Sunday. In the late 19th century, however, a French archeologist discovered a copy of the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, which clarified the time when Jesus rose as recorded in Matthew’s gospel.

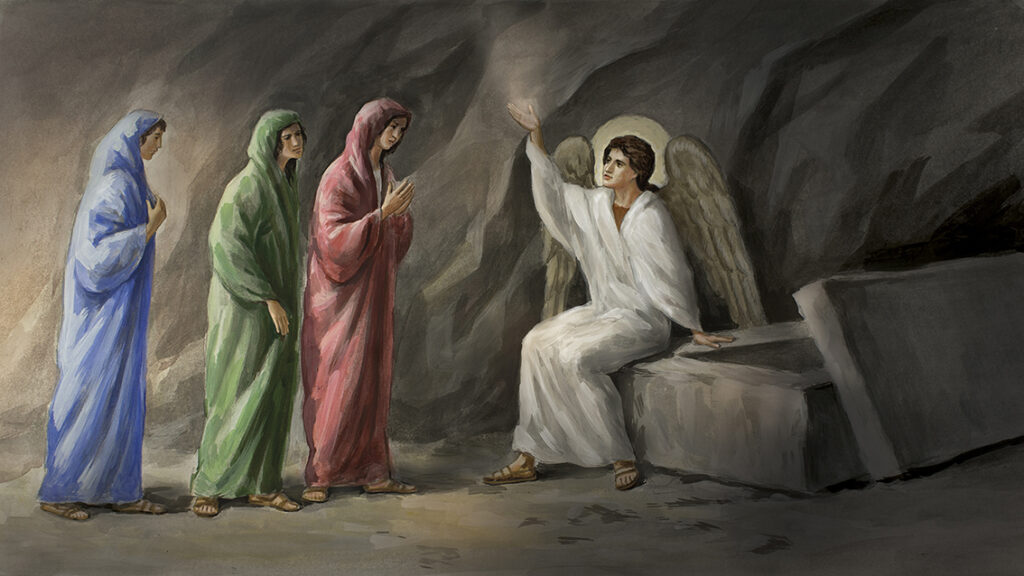

The Gospel of Matthew says, “After the Sabbath, as it began to ‘shine on’ (ἐπιφωσκούσῃ) toward the next day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary came to look at the grave, and behold, there was a great earthquake, for the Angel of the Lord descended from heaven and came and rolled away the stone.”Matt 28:1

It was the preparation day, and the Sabbath was shining on (ἐπέφωσκεν), about to begin.

Luke 23:54

The Jewish days end at sunset. This is when a new day “dawns.” The sunset in Matthew is described by an obscure Greek word, epiphóskó (ἐπιφώσκω), which means “shine on.” This word is only otherwise used in Luke 23:54 to describe the evening when Jesus died: “It was the preparation day, and the Sabbath was shining on (ἐπέφωσκεν), about to begin.” The so-called Gospel of Peter, originally written in the 2nd century, used the same word “shining on”7 (ἐπέφωσκεν) to describe sundown, when Jesus was buried and rose again. This agrees with all accounts of the New Testament.

To summarize the events recorded in the Gospels, at sundown on Saturday evening, the two Marys went to the tomb and found out that the stone had been rolled away and that Jesus had risen. Later, while it was still “early,” still dark, the two Marys and Martha went to the tomb.Mark 16:2 John 20:1 Finally, “at dawn (ὄρθρου), “the women who had come with Him out of Galilee” (Luke 23:55) went to the tomb, as described in Luke 24:1.

31. The True History of Sunday

Today, those who support the idea that Sunday was observed by the early Church assume that the “Lord’s Day” in Rev 1:10 describes Sunday as the day for communion. In fact, however, there is no evidence that the early Church had a special meeting on Sundays.

The phrase “the Lord’s Day” as a weekday is found only in false translations and in false writings attributed to early Christian writers. Socrates Scholasticus, in his 5th-century Church History, said that all the churches in the world observed communion on the Sabbath day, “yet the Christians of Alexandria and Rome, on account of some ancient tradition, have ceased to do this.”8 According to Socrates, even the churches of Alexandria and Rome originally observed communion on the Sabbath day. In the 6th century, Sozomen repeated this claim in his Ecclesiastical History.

God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. So the evening and the morning were the first day.

Genesis 1:5

We know that in the 2nd century, the Church at Alexandria and some other Egyptian churches observed communion on Saturday night, as described in the Epistle of Barnabas.

The “ancient tradition” of Sunday communion in Rome began after Justin Martyr told the Emperor that the Christians in the cities and in the country observed the Lord’s supper on Sundays.

In A.D. 150, Justin Martyr was living in Rome and wrote to the Emperor, saying, “Sunday is the day on which we all hold our common assembly because it is the first day on which God, having wrought a change in the darkness and matter, made the world, and Jesus Christ our Savior on the same day rose from the dead.”9

None of Justin’s statements, however, were true. None of the churches met on Sundays for communion, Jesus did not rise on a Sunday, and this was not the day when God made the world. These were all Saturday events. It seems that Justin Martyr equated the Jewish first day of the week to the Roman day Sunday for the emperor’s convenience.

32. The Image and Mark of the Beast

Both the mark of the beast—Sunday rest—and the image of the beast—the Trinity doctrine—had their beginnings in the First Apology of Justin Martyr to the Roman emperor. Justin Martyr equated the events of Saturday evening (the Jewish first day of the week) to Sunday, and said that the holy spirit on Christ was a third person10 called “the Spirit of Prophecy,” who was born on the waters in Gen 1:2.11

Justin Martyr’s theory made the anointing of God on the Church to be another “person”—a third person. This was a great departure from the understanding of the Jews, who said that the Ruah of God in Gen 1:2 was the breath of God described in Ps 33:6 and Job 34:14.

If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives a mark on his forehead or on his hand, he also will drink of the wine of the wrath of God,

Revelation 14:9-10

Because Justin Martyr wrote his First Apology from the church in Rome, these two errors were proclaimed as doctrines of the Church. In about A.D. 229, Origen of Alexandria, in his Commentaries on John, said, “All things were produced through the Word, and the Holy Spirit is the most excellent and the first in order of all that was produced by the Father through Christ.”12 In his Homilies, Origen said, “On Sunday, none of the actions of the world should be done.”13

In A.D. 321, Emperor Constantine declared Sunday a day of rest, and in A.D. 381, the Trinity doctrine became the official doctrine of the Catholic Church.

The image and mark of the beast are two significant themes of the Book of Revelation. Both false teachings are refuted in the first chapter. The Lord’s Day in Rev 1:10 does not refer to Sunday, as the Church later claimed, and the many manifestations of the Spirit of Christ in verses 13–16 explain the true relationship between Christ and God in the Bible. Christ was the Word, the firstborn spirit, whom John called “the beginning of the creation of God” in Rev 3:14.

- From Sabbath to the Lord’s Day, D.A. Carson, 1999, pg 384 ↩︎

- Eusebius, Church History, Book 5:24 ↩︎

- De Corona, Chapter 3 ↩︎

- Origen, Contra Celsum, Book VIII, Chapter 22 ↩︎

- On Idolatry, Chapter 4 ↩︎

- Eusebius, Church History, Book 3.27 ↩︎

- Gospel of Peter, vs 35-37 ↩︎

- Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, Book V, repeated by Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, Book VII ↩︎

- First Apology, Chapter 67 ↩︎

- First Apology, Chapter 13 ↩︎

- First Apology, Chapter 60 ↩︎

- Commentaries on John 2:6 ↩︎

- Homil. 23 in Numeros 4, PG 12:749 ↩︎